Seeing the Suppression: Mapping Local Internet Control

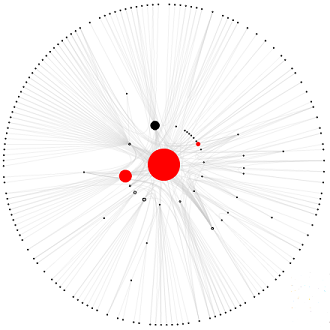

The Mapping Local Internet Control project launched last week by the Berkman Center for Internet & Society illustrates the ability of Internet users within a particular country to access the global Internet through their Internet Service Providers (ISPs) or other Autonomous Systems used to route web traffic. One of the key findings of this project is that approximately 96% of all web traffic in China is routed to websites hosted within China. So why is this significant?

This mapping is able to demonstrate one of several means that Chinese authorities use to restrict content online - through centralizing Chinese web traffic to 4 points of control (ways to access the Internet), Chinese authorities can more readily curtail access to any content deemed objectionable.

Visualization of how this control takes place in China is even more striking when compared to other countries guilty of censoring independent content online, such as Iran and Russia. This visualization on the nature of accessibility in China is especially valuable, given the more limited information available on mapping online discourse in Chinese when compared to research on the Arabic, Persian, and Russian blogospheres.

However, as Hal Roberts addresses in his blog entry on the report, there are certainly other factors that could contribute to this phenomenon of funneled Chinese web traffic. He states, “The extremely high proportion local web traffic in China may be the result of the success of the Chinese government in blocking the international sites, like Facebook, YouTube, and Blogger, that are generally the biggest destination in other countries. Or it might be because Chinese people like to read content written in Chinese by other Chinese about Chinese topics run by Chinese people. It is likely some combination of the two factors.” This combination that Roberts highlights has certainly gained attention in other areas over the years: the dominance of China’s Baidu search engine over global counterparts in the Chinese market, as well as the array of localized social networking tools for Chinese Internet users that offer similar functionality to their international equivalents. Another symptom of this control is the creation of vocabulary designed to evade keyword filtering while criticizing the Chinese regime.

It is important to point out that the routing of web traffic through a limited number of access points is only one example of curbing online discourse within a country’s borders. Sadly, use of physical intimidation, financial pressure, and abuse of rule of law are increasingly commonplace to quell Internet activism in repressive environments like China. Even Roberts notes this trend, stating, “There is no need to launch a DDoS attack against a dissident site that is hosted within the offended country when agents of the offended country can simply knock on the door of ... the individual activist publishing the content...”

While the cat-and-mouse game of Internet censorship continues in several countries, projects such as Mapping Local Internet Control, which illustrate the extent of techniques for censorship and surveillance of Internet users, illuminate the opaque efforts to control web traffic within a country’s borders as well as enable activists to strategize ways to counteract these methods of control.