Talking "Liberation Technology" With Friends at Stanford

Last Friday I had an opportunity to talk to the Liberation Technology Seminar at Stanford University - led by democracy scholar Larry Diamond.

The talk, titled "Seize the Day, Seize the Data: Tech-Enabled Moments of Opportunity in Closed Societies," provided a great opportunity for our team here to shore up our thinking about working in what we call challenging environments or closed societies. You may think of them as authoritarian regimes.

Working in closed societies is a small percentage of NDI's work; the majority of our programs take place in established democracies of varying levels - from the most fragile to well established democratic countries. However, in response to the State Department's Internet Freedom initiative and other factors, we have seen additional interest in this topic (as I have mentioned) and it's a good opportunity to share how NDI approaches ICT work in these countries.

The text of our talk is attached below, and the video will be available soon. Here is a summary of the four main points and the QA.

Rights-based Approaches and Moments of Opportunity

In closed societies we advise our civil society and political party partners to create long term “rights-based” strategies whose goals are change in legal framework in their country that respects human and political rights, and whose methods are peaceful political reform and creating more political space.

Activists and civic groups need to plan for the long haul because change is most often gradual, but good preparation can help them to take advantage of moments of opportunity to advance their work. These moments of opportunity can sometimes be created by identifying an upcoming event with political significance, such as an election or public holiday, then using this event as an opportuinty to share evidence of abuses by their government.

Documenting abuses and exposing them to citizens in their countries - and the international community - at the moment when the world's attention shifts to their country is sometimes an effective way to pressure closed government to improve human and political rights.

In the business we call approaches like this “political process monitoring” and there are basically three steps:

- Collecting, compiling and analyzing information;

- Developing and disseminating findings; and

- Using the findings to raise public awareness and government responsiveness.

I went on to talk about how technologies can play an important role in increasing the effectiveness of these stages. I'll write a separate post on this approach with some of the details, and link from here.

Programming: Tech-Enabling Not Tech-Driven

In the second part of the talk I shared a successful strategy that our team here has settled on over the years to “tech-enable” programs combining appropriate technologies with strong political organizations and established organizing methods.

A tech-enabled program uses technology as an enabler. It is combined with effective traditional program strategies to create a multiplier effect on program impact. The technology tool is introduced into a specific environment designed to improve impact; in the absence of the technology the approach still works - but to lesser effect.

We avoid tech-driven programs and technology “drop-off” approaches - even when we've got very promising technologies.

A “tech-driven” approach refers to identifying a promising technology tool that you then try and work into programs, or even provide the tool in the absence of a program at all and expect change to occur based soley on the fact that the technology was introduced. Tech-driven programs most often require changes to the program to accommodate the technology that make the program less impactful because more often then not the tool does not fit the need very well.

It's always important to be reminded of the old adage, "when all you have is a hammer, everything starts looking like a nail".

So we challenge ourselves to apply the following formula as a check - are all three components in place?

Strong organizations + good organizing methods + enabling technology = good program outcomes

More on that approach here.

The 2008 Zimbabwe elections provides a good example of this appproach.

Risky Business, Working in Closed Regimes

After an impromptu question session, I shifted the conversation to security.

The first point here is always that we take security of our partners and our staff very seriously, and plan our programs accordingly and responsibly in repressive states. We believe that authoritarian regimes have the upper hand and activists and NDI staff must be pragmatic by employing security and program planning approaches appropriate to that environment. We have an established framework for planning programs in closed societies and we use it, detailed in this post.

And it's critical not to forget that citizens who participate in politcal movements, such as protests, are not typically trained in using technologies in ways that protect themselves - and widely used technologies like mobile phones, digital cameras, social network platforms and using Internet cafes can put them at great risk in some societies. Citizens who participate but don't use any technology at all can also be at great risk depending on how others use digital technologies.

I'll detail thoughts on this topic in a separate post and link it from here.

Fragile Democracies, Big Opportunities

I closed the talk with a reminder that it's important not to focus exclusively on closed societies at the expense of fragile democracies - democracies where political space may soon close and the society become closed, the regime more authoritarian (also covered in this post). Despite the security cautions just discussed, technologies are very important for democratic development – not only because they can help citizens in non-democratic societies, but because of the important role they can play in consolidating democracy in fragile and transitional democratic states.

Fragile and transitional democratic states are environments where space for civic and political engagement exists, but where democracy hasn’t fully taken root. These states risk backsliding toward authoritarianism if nascent democratic institutions are not strengthened.

Societies with emerging but fragile democratic systems provide a “window of opportunity” where the political reform process can be supported more effectively than in non-democratic societies, where specific “moments” need to be skillfully identified and leveraged.

During and after my prepared remarks, there were several great questions and tweets about NDI's work generally including some healthy skepticism from Stanford Knight Felllows @farano and @WendyNorris and discussions about the political situations in the caucuses, North Korea and Zimbabwe.

In addition to the questions midway through the presentation (video minute 25 or so) and the questions at the end, @LeighAnne3000 asked a question on twitter:

@LeighAnne3000: @cspence thank you for the talk today at Stanford. I have a question: how do you help government workers in fragile democracies?

@cspence: @LeighAnne3000 @NDI governance programs seek to create strong, democratic, public-sector institutions . See: http://bit.ly/brsCzs

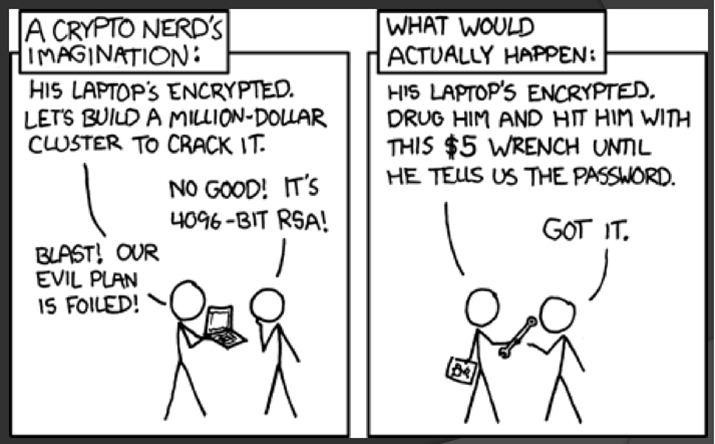

Cartoon above courtesy of XKCD - http://xkcd.com/538/