Technology Strengthens Citizens Watchdog Role in Indonesian Elections

Editor’s Note: This is a guest blog post by David Caragliano, Program Manager on NDI's Asia team.

In any democracy, a close election tests the durability of the country’s political institutions and rule of law – witness the U.S. presidential election of 2000 and Bush v. Gore. By many accounts, after Indonesia’s contentious July 9 presidential election, the institutions of the world’s third largest democracy appear to be holding up well. Joko Widodo (familiarly referred to as “Jokowi”), a candidate of relatively humble origins, defeated former special forces general Prabowo Subianto by a six percentage point-margin of victory. Prabowo has alleged “massive and systematic fraud” and has filed a lawsuit disputing the results in the country’s Constitutional Court.

Prabowo will likely argue for a recount in certain electoral districts (we will wait to see whether his lawyers invoke “hanging chads”). But, through an amalgam of established practices and improvizations, Indonesia’s electoral agencies and civil society have relied upon a number of tactics – leveraging social media, online crowd-sourcing and data aggregation – to help ensure an inclusive, accountable, and transparent process.

Election observers present in many of the polling stations in Indonesia’s population centers helped to safeguard the electoral process, although inevitably there have been gaps in coverage. Election monitoring in Indonesia is not new; monitors have observed the polls in all of Indonesia’s elections since 1999. While foreign observers were largely absent in this election, nonpartisan citizen observers and party agents were present from the opening of the polls through the vote count at many locations.

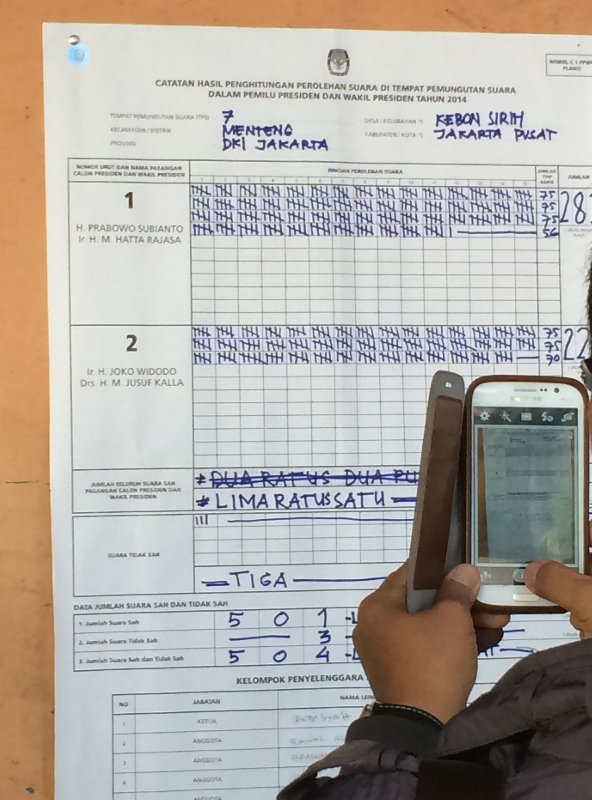

Outside scrutiny by election observers generally provided a first line of protection against fraud at the polling-station level, where an old-school, manual vote tabulation system was used (Governor-level elections have introduced e-counting systems and following the introduction of a biometric national identification card in the near future, the Election Commission may introduce e-counting at the national level). After the polls closed on July 9, polling officials with citizen observers as witnesses emptied ballot boxes and one-by-one, manually examined each ballot, entering tallies for each candidate on the C1 form, the official record of the results at the polling station-level. Polling officials publicly posted the C1 forms; election observers and citizens were able to take pictures and upload them to social media. The manual tabulation continued for nearly two weeks as officials at the village/ward, sub-district, district and finally national-level added up the tallies for each candidate.

The delayed announcement of the results and the lack of transparency during the tabulation process at subsequent levels raised concerns of fraud. With the aim of policing improprieties, both the Election Commission and citizens aggregated results data posted online on a number of websites. While not legally binding, these crowd-sourced records have allowed for a high-degree of public participation in crosschecking results and may prove useful in the event of a recount. In order to counter manipulation during the official vote counting, one website, Kawal Suara, allowed web users to access the uploaded C1 forms at random and re-enter the results. If there were different data entries for the same document, the system used the number with the highest frequency. Each IP address could only input one document from each polling station. Kawal Suara crowd sourced a vote count all the way up to the national level.

“Quick counts” (also known as parallel vote tabulations or sample-based observation) provided an additional layer of independent oversight. Quick counts are a systematic method of election observation, which allow analysts to predict the results of an election. With a sample of 2,000-4,000 of the country’s 478,685 polling stations, statisticians can predict the results of the election within a 2 percent margin of error. Observers deployed to a representative sample of polling stations across the country and after finalization of the C1 forms, they reported the results numbers to pollsters’ data centers for analysis (in contrast, exit polls are based on interviews with voters at a sample of polling stations).

Quick counts have become a standard part of the electoral process in Indonesia, appearing in nearly every television and print media news outlet following the election. Quick counts first gained traction in 2004 and ten years later, 56 groups registered with the Election Commission to carry out quick counts. The historically reliable firms compiling quick counts lend credence to official results consistent with their findings. In some cases, such as the Jakarta 2012 gubernatorial race, candidates have conceded defeat based solely on quick count results. In this presidential election, the first quick count results were announced hours after the polls closed, immediately filling the void as the official results were being compiled.

The quick counts in the July presidential election were not unanimous, however, and this has led to an inference of partisan bias among certain media outlets and polling firms. Countervailing voices in the media and civil society have sought to contextualize the dueling quick counts. The eight most reputable polling firms called the election in favor of Jokowi by a margin of roughly five percent. TVOne, a television station that only aired quick counts from lesser known pollsters without the same track record for accuracy, called the election in favor of Prabowo and received a barrage of criticism on social media.

The wave of condemnation increased after the head of the polling firm Pol-Tracking Institute said his organization had backed out of its contract with TVOne early on the morning of the election after the station insisted on including the results of less reliable pollsters. Experts have questioned the methodological credibility and the financial independence of the pro-Prabowo pollsters, and the Indonesia Association for Public Opinion launched a probe into the results methodologies of the quick counts run by its members Policy Research Center (Puskaptis) and the Indonesian Voter’s Network (JSI), whose results showed a Prabowo victory.

Notwithstanding the highly charged atmosphere, citizen participation in election monitoring, as well as the crowd-sourced vote tabulations and the existence of credible civil society organizations with the capacity to conduct quick counts have all contributed to an environment where the Election Commission could more readily weather political pressures and conduct the official tabulation process in an independent and nonpartisan way.